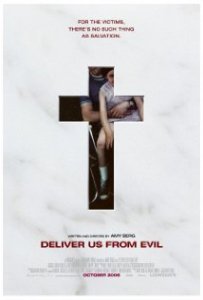

Deliver Us From Evil is a competent, straightforward documentary by a filmmaker with a background in television journalism on a grave and disturbing subject, with some really powerful emotional moments.

The subject is the epidemic of sexual molestation cases by Catholic priests. The movie focuses primarily on a specific priest and his misdeeds, but also uses that to some extent to address the general phenomenon. The priest himself is interviewed extensively, and we also hear from or about some victims, family members of the victims, people in the church hierarchy who covered up the offenses, a maverick priest fighting the hierarchy on this issue, academic commentators, and others.

I have to say, I have a lot of respect for the victims and their families (and the perpetrator for that matter) who agreed to open up and talk about these experiences on camera. This has to be one of the hardest of experiences to talk publicly about, but their willingness to do so is very helpful in furthering understanding of these issues.

The most intense moment of the film for me was watching the father of one of the victims break down and cry more than once when recounting how devastating the experience was for the family.

I found the priest himself fascinating. Maybe he fits a certain psychological “type,” but none that I recognized.

He’s not evasive. Well, people might argue that he’s evasive or in denial about some of the nuances and some of the ramifications of what he’s done, but I mean as far as basic facts he’s open and straightforward about it all. He states what he did, how he did it, what his mental and emotional state at the time was, who attracts him and doesn’t attract him sexually, and so on. He doesn’t downplay it, brag about it, or try to explain it away. He just states it all quite openly.

When he’s asked directly about any abuse in his own childhood, he reveals he was molested by a priest himself at least twice, as well as engaging in apparently consensual sex with two siblings. (Yes, I know it doesn’t count as consent for legal purposes.) But he doesn’t bring those experiences up on his own, or present them as any kind of excuse for his own later behavior.

He’s of a moderately cheerful disposition. I don’t know that I would describe him as emotionally detached when he speaks about these matters, but perhaps in a relative sense he is. That is, he speaks with a certain amount of feeling, acknowledges what he did was wrong, talks about his own internal struggles at the time, and so on, but there’s an ease and even a contentment about him that seemingly doesn’t fit the gravity of the subject matter, and that will unnerve some viewers. It doesn’t appear to be something that’s difficult for him to talk about, or something that stirs up powerful emotions. Which some will take as an indication that he still doesn’t “get it,” still doesn’t really appreciate how bad what he did was.

Or maybe people will see it as an indication that he’s lying, that he’s hiding what he really believes and feels. I don’t read it that way; he seems quite sincere to me. But I’m not an expert in psychology; maybe he is some kind of con man who’s seeking to deceive the viewers.

But overall he doesn’t come across as “off” to me, as someone who has some major mental illness. Or as someone who’s just morally evil and sadistic. Or however I’d have expected a serial pedophile to come across.

It’s hard to put myself in a pedophile’s shoes and really understand what they’re about. And not even so much because of the being sexually attracted to little kids thing. That’s no harder to imagine than imagining being gay or whatever. People are turned on by all kinds of different people and different fetishes and all that. I know how I respond to Scarlett Johansson, so it’s just a matter of imagining feeling that way when I see a six year old.

No, the more puzzling part for me is why one would act on the attraction. And not so much with a sixteen year old cheerleader or something—anatomically that’s for all intents and purposes a woman; it’s just a cultural thing to set the age of consent a little above or a little below that. I mean with the sort of victims this priest molested, which included literal infants.

I mean, I’m attracted to 20 year old women. I also recognize that my chances of having consensual sex with a 20 year old woman at this stage of my life (leaving aside prostitution, I suppose) is something like 0.0000001%. So my choices are to have morally and legally wrong sex (i.e., rape) with them, or to not have sex with them. For obvious reasons, I choose the latter.

You know, you don’t necessarily get to have sex with whatever type of person you’re most attracted to. So have sex with someone else. Or if you don’t like that option, then don’t have sex. It’s not the end of the world.

That’s what I have more trouble grasping. Not that people are attracted to this or that, but that they’d be willing—dozens of times in the case of this priest—to act on that attraction in ways that they know cause substantial harm to others.

As I was watching this movie, probably what was on my mind as much as anything was comparing my own reactions to what I believe would be the typical reactions of other people, and contemplating how out of step I am with people in so many respects.

One, I don’t think sex offenses, including sex offenses involving children, are as horrible as American society now regards them. It’s commonplace nowadays, for example, to insist that such crimes are worse than murder. I strongly disagree. I don’t think it’s even close.

If this had been a case of, say, dozens of children disappearing over the course of years and then turning up dead, and then the priest was discovered to have been a serial killer who murdered them all (and a huge number of other priests were engaged in comparable killing sprees at the same time), then I take it most people would regard that as equal or in fact milder than what really happened. I would take it as vastly worse.

I’m not saying sex offenses aren’t bad; I’m just saying they’re not as bad as society now seems to regard them, and not as bad as murder.

My reaction is in part based on the fact that there’s still some choice over how to react to a sex offense. A murder is a “sticks and stones” offense. You’re dead. It’s not that you choose to regard yourself as dead, or that your being dead is a social construct. You’re just dead. Whereas sex offenses are a combination of “sticks and stones” and “words,” where some damage is objectively inflicted, and some damage depends on how the act is assessed. Some such offenses, like anally raping a two year old, contain much more of the “sticks and stones” element, and others, like leering at a seventeen year old girl and grabbing her ass on the street, contain much more of the “words” element.

Consider, for instance, a society in which it is considered the greatest shame to a girl and to her family for a stranger to see her unveiled face before she turns eighteen. If there were an eleven year old girl who was surreptitiously peeked at unveiled, one can imagine it being a huge deal and utterly traumatizing her in a way that she never fully gets over for the rest of her life.

But there’s a certain artificiality to that harm. Society doesn’t have to frame the act of peeking that way, and she doesn’t have to react to it that way. But it does and she does, and so it’s a huge deal.

We hammer home the message that if you’ve ever been the victim of anything currently classified as a sex offense, especially in childhood, that you have been insulted and dishonored and abused in the worst way imaginable. So naturally people feel shamed and traumatized and vengeful and all the rest.

Not to say they wouldn’t feel those things without that message, but I’m skeptical that they would feel them to the same degree. I don’t think sex offenses would suddenly become non-harmful if we simply all shrugged them off as no big deal. But I suspect some of their harm—maybe 1% for some offenses, maybe 80% for others—is a social self-fulfilling prophecy like that.

A person who is raped is less damaged than a person who is murdered. A person who is raped is possibly more damaged than a person whose leg is shattered by being hit by a drunk driver and who walks with a painful limp the rest of her life, but if so it’s in part due to non-necessary attitudes and reactions of society and the victim herself. I think there’s less inherent damage, and it’s the “add-on” damage that potentially reverses the order.

Anyway, that’s my highly unpopular take on that, which will be easily dismissed by most as indicative of the fact that I, like the priest himself, just don’t “get it.” But as far as that goes, I’m especially appreciative of the movie’s inclusion of the perspective of the victims and their families, because if I’m ever to “get it” that molestation is objectively worse than murder and such, then presumably it’s listening to and empathizing with folks like them that’ll take me in that direction.

Two, as I previously mentioned in at least one of these essays, I’m not much for “piling on” and hating people, or the types of people, that everyone else already hates. Maybe it’s something contrarian in me, maybe it’s a connection to the underdog or whatever, but when everyone is bashing someone and trying to top each other in elaborating how horrible the person is and what tortures and suffering they deserve for their ill deeds, I find myself at least as uncomfortable with the mob hatred as with the initial wrongdoing.

Put me in a situation where females are treated as non-human property for men to abuse for their pleasure, and where people who molest and rape little girls are laughed with and celebrated for their derring-do, and I’ll be suitably outraged. Put me in a situation where everyone already hates them, and I’m on the lookout for how this mob mentality is going to lead to a witch hunt, damage civil liberties, weaken the rights of the accused, embitter and damage the haters themselves, etc.

I’m a lot more troubled by evil that other people don’t see as evil, or that is a matter of controversy as to whether it’s evil. I think a lot of religion itself is more inherently damaging than sexual molestation. A priest who spends the same amount of time and effort influencing children’s attitudes in the direction of homophobia, or keeping women in traditional gender roles, or distrusting science and rationality and clinging to supernaturalism, or following a morality based largely on sexual prudery and taboos, and so on, as this priest spent on molestation, to me does more total direct and indirect damage to the world and to human happiness.

I’m not much of a hater, so I would try not to hate either of them. But I’m equally or more outraged by that hypothetical Pat Robertson-type as by this priest.

Three, I suspect I’m more willing than most people to see someone like the priest as a mixed bag of good and bad traits. I think for a lot of people, once they’ve categorized someone as being in some supremely evil group, like “sex offender” or “child molester,” then it follows that they have to lack any good qualities, since nothing good could be compatible with being the kind of person who could do such terrible things. Terrorists are always “cowards,” for instance, because courage is a positive trait, and nothing positive may be attributed to someone of that category.

Whereas I can listen to the priest and at least entertain the possibility that he’s manifesting sincerity about this, or manifesting courage in admitting that, or that he was being kind back when he did this, or is doing the right thing in seeking to make amends by doing that, etc. Or he may be a son of a bitch in every possible respect, but I don’t think his having or lacking admirable qualities is determinable solely from his being a sex offender.

Four, just as I’m not big on the whole hate thing, I’m mostly not a revenge kind of person. If someone has done horrible things from Point X to Point Y, what I’d most like to see is for him to be the best person he can be from Point Y on. Which is exactly what I’d most like to see from someone who hadn’t done horrible things. My priority isn’t to see to it that he suffers from Point Y on in a way that somehow reflects the horrible things he did from Point X to Point Y.

If I were to be for harsh treatment at all (I’m not), then it would have to be for future-oriented reasons of deterrence and such. That is, that that way of reacting to his wrongdoing will somehow lessen the frequency and severity of comparable acts of wrongdoing in the future (without generating equal or greater deleterious consequences of other kinds). It wouldn’t be for the past-oriented reason of somehow gaining satisfaction seeing him suffer for what he did.

Five, I have the sense that whatever someone like this priest says or does now, most people will react as if that makes it worse, or constitutes further evidence what a horrible person he is.

Maybe I’m mistaken about that, but I think there’s a certain logical incoherence to people’s attitudes in that respect. It’s like the joke about how bookies like to lament their ill fortune and insist that they can’t catch a break:

Bookie: Say, do you know how that Yankee game came out?

Man: The Yankees won.

Bookie: Oh God, I got crushed! I knew that was going to happen. Everyone and his brother was on the Yankees!

Man: No, no, wait. I misspoke. The Yankees lost.

Bookie: That’s even worse!

Just thinking it through, it’s hard for me to imagine anything he could do or say that people wouldn’t point to as all the more reason to condemn him.

He openly talks about what he did? He’s bragging. He’s making it worse for the victims by bringing all this up again.

He refuses to talk about what he did? He’s in denial. He wants you to think he’s innocent. He’s refusing to give the victims closure by speaking the truth about what happened.

He says what he did was wrong? He’s lying. He’s saying what he thinks people want to hear so his treatment will be milder.

He tries to justify or excuse what he did as not wrong? Only a monster could not see how wrong what he did was, and try to deny responsibility for it.

He shows little or no emotion? Only a monster could feel nothing after what he did.

He breaks down in tears of self-loathing? Crocodile tears. He’s making matters worse with this phony display.

He reaches out to the victims and attempts to apologize and make amends? How clueless and evil can this guy be not to realize that the last thing in the world they want is further contact with him, or any message from him?

He does not reach out to the victims and attempt to apologize and make amends? Obviously he sees nothing wrong in what he did and no reason to try to mitigate the damage he’s caused, which makes him even worse.

Let me be very clear. I don’t mean just that people would have the attitude that nothing he can do or say now would make him a good person or undo the horrible things he did. That—whether true or false—is not a logically incoherent position.

What I mean is while I watched him in this movie, I pictured people reacting to it by citing everything he did and said as “making things worse” or providing confirming evidence for their beliefs that as a child molester he can have only bad qualities. But then I imagine a parallel movie where he says and does precisely the opposite of what we see in the interviews in this movie, and I can’t help but picture viewers responding the very same way.

I think once you’ve given yourself over to hating someone, or some group, it’s easy to shape all incoming evidence to provide further justification for that hatred.

Anyway, I just see myself as wildly out of step with the masses on this stuff. But I’ve rambled on about it long enough, so let me move on and make a few other quick points about the movie itself.

I mostly agree with the filmmaker’s obvious contention that the Catholic hierarchy responded inexcusably to this case, and to the phenomenon of sexual abuse by priests in general. I don’t know that the analogy of the Mafia fits all that well, because that implies violent silencing of witnesses and that kind of stuff, but the analogy of a lawyered up amoral corporation strikes me as pretty apt.

There are some interesting points made along the way that struck me as thought-provoking and at least somewhat plausible, but needing further examination and thought before I’d feel comfortable accepting or rejecting them.

One is that the Catholic Church’s strange underreaction to the whole crisis is in part because according to the doctrine of priestly celibacy, all sex by a priest is equally wrong. So yes, it was bad for this priest to molest dozens of children, but that calls for no more harsh a reaction than if he had had consensual sex with one of his adult female parishioners.

Another is that, again due to the doctrine of priestly celibacy, priests are vulnerable to a kind of sexual arrested development. They try to shut down that whole part of themselves, sometimes from a very early age, so their desires don’t develop in the normal ways, they don’t have the normal experiences, they don’t learn from the normal mistakes. As one commentator puts it, it’s not a surprise if priests who commit sexual transgressions are disproportionately pedophiles, because in effect they are drawn to people at their own level of psychosexual development, which typically would be children.

I also think you have to be struck by the sheer magnitude of the phenomenon. I believe the figure given in the movie is that something like 100,000 people in the U.S. alone now claim to have been sexually abused by a priest in their childhood. If you assume—as the evidence indicates for this kind of thing—that the number of people who come forward to report the abuse is dwarfed by the number of victims who remain silent, and if you think about the fact that there are also all the incidents outside the U.S. to consider, it boggles the mind just how much sexual abuse is being committed by that one little subset of the population. Which then makes it especially urgent to ascertain what it is about that subset that makes that the case. Maybe it’s the celibacy requirement, maybe it’s the hierarchical structure of the religion and the way it influences its lay members to be trusting and deferential toward its clergy, maybe it’s something else. But clearly there’s something going on.

Deliver Us From Evil is a good solid documentary. It’s interesting and it provides a lot to think about. I’d put it up there at least on the level of Lake of Fire.