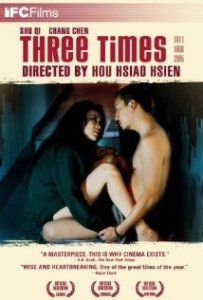

Like Tickets or Amores perros, Three Times from director Hsiao-Hsien Hou is divided into three separate stories. Unlike those two, its stories are unrelated to each other. (Well, thematically related, but the events don’t overlap as in those other two movies.) Unlike Tickets, it is not a collaboration of three different directors doing one segment each.

Using the same primary actor and actress, the movie consists of three stories of love and courtship, all set in Taiwan, but in three very different historical periods.

The first takes place in 1966. A soldier kills time in a pool hall while he waits to ship out. He befriends a young girl who works there.

I call it a pool hall, but I’m really not sure what the establishment is. It appears to have a grand total of one pool table, though that’s not a hundred percent clear because it’s shot in close-ups and you never get a full view of where they are. But I don’t see a bar (though there may be one) or much of anything else. It almost looks like the lobby of a very small hotel where they’ve squeezed in a pool table.

The custom (because one or two other such establishments are shown later) seems to be for a girl to act as a kind of hostess and to play pool with the customers. Maybe just customers who don’t have anyone to play with, but it seems like the employee plays pretty much all the time. It has the feel of something like a “bar girl” paid to sit at a bar and talk to the customers and keep them company.

So anyway, they make a slight connection, and agree to write to each other while he’s away, which they do.

He returns sometime later on a brief leave from the army, and must search far and wide for her, as she no longer works at that pool hall.

The second story takes place in 1911 in what I’m thinking is a brothel, though again I’m not entirely sure. This time the young man is some sort of a liberal journalist or intellectual, and the young woman is again an employee of the establishment. If he’s buying sex from her that’s not at all clear; it seems like he just comes by regularly to relax and chat with her and drink tea in a sort of parlor.

She shares with him on one of his visits that another girl (I believe a co-worker in the brothel or whatever it is) is pregnant, and it’s undetermined if they’ll be able to put together enough of a dowry to get the man who impregnated her to take her on as another wife. So the journalist gallantly donates enough to solve that problem and the girl gets married.

On principle he’s opposed to the whole multiple wives/dowry customs, but he decides in an individual case he’s more concerned about the outcomes for the people involved, and he knows what will happen to a young girl having a baby out of wedlock in that culture.

The third story takes place in 2005. Honestly my mind was wandering more watching this one and I didn’t follow it all that well. But it’s about a photographer dating a girl with epilepsy. If I understood it correctly, the girl is also in a relationship with a female lover.

To me what’s most notable about this film is the style. The content is OK here and there, but the style is what would make me remember it.

It’s a style that somehow makes the film both more slow and tedious, and more intriguing.

For one thing, there is much less dialogue than in the typical movie. But when I think of other movies I’ve written about of which I could say that (e.g., Man Push Cart, Gus Van Zant’s Elephant and Paranoid Park, Day Night Day Night), it really doesn’t feel much if at all like any of those.

Maybe because it’s so smooth and so natural. It doesn’t feel like dialogue has been artificially removed for some artistic reason; it just feels like a lot of the film focuses on times when people aren’t talking.

The cinematography in general is really good. I’m usually not that visual a person; I’m far more focused on the ideas and such in a movie. But there’s a lot in this film that’s simply beautiful. And I don’t mean just a beautiful landscape or something conventional like that, but the way the billiard ball slowly rolls down the table, the play of the red brake lights in the Taipei traffic—it’s like every shot is arranged so carefully and so masterfully.

As I say, the long periods of silence have conflicting results, for me anyway. On the one hand, there’s less going on, so it’s more boring. Honestly, I don’t know how many more two hour foreign films of this style I’d want to sit through.

On the other hand, at times I felt a greater appreciation for the other aspects of the film because there is more opportunity to contemplate them. I don’t know that I would have been as conscious of the visual loveliness of this film if I had been reading subtitles the whole time and my brain had been busy processing that type of information. And what dialogue there is seems to have more gravity precisely because there’s less of it. It’s natural to pay more attention to it and discern its nuance.

In the first vignette for instance (by the way, I found the first the best, then the second, then the third—not sure how much of that reflects differences in quality and how much is just that I was losing patience the longer the movie went on), I found the pool playing strangely fascinating. They’re mostly not talking about it, and it’s not like there’s some specific match you see start to finish like a sporting event where you can root for somebody, but there’s something mesmerizing in the movements. At times they seem to be playing billiards, at times snooker, and at times maybe American-style pocket pool, but for whatever reason I really wanted to figure out what they were playing. It isn’t just something unimportant going on to give the characters an excuse to interact; it naturally drew my attention.

For another example, in both the first and the second pieces, there is something appealingly quaint and charming about how the main characters are on their best behavior and maintaining a certain respectful distance. The silence is at times a shy, meaningful silence, like they’re just appreciating each other’s company and that’s enough.

In the first one, when the soldier is about to have to return to his base, and they wordlessly, slowly reach out to each other to hold hands, it’s a really sweet moment.

At the end of the second story, the woman—kind of hesitantly like she really is trying not to be too forward—asks the man if, vaguely analogously to how he was willing to act generously to help out her co-worker in spite of what he might feel about the social customs at play in the situation in general, he sees she and he as possibly having a future together that would take her out of this place. And he musters up little or no response as they continue to sit together.

But the silence says as much or more than words could. Watching his, or really their, facial expressions, body language, etc. is fascinating, because there’s just so much going on in that moment. He’s uncomfortable in a sense, but it’s not like he’s offended by the suggestion, or finds the idea of being with someone socially inferior to be personally unpalatable. It’s more of a sadness as he’s brought face to face with the fact that he genuinely likes this person and in a way would very much want to be with her, but he just can’t bring himself to violate whatever class/social/familial rules and expectations that that would entail, even if his liberal principles tell him he should do so. And on her part, there’s nothing angry, nothing accusatory about his being a hypocrite, just again a sadness, like “Well, I thought and hoped maybe it could be otherwise, but I know it can’t.”

It’s a bittersweet moment, because you feel both the fact that their connection has been a good and genuine one, one where they have each contributed something positive to the other’s life, and the fact that there can be no more of a connection beyond that for them. All conveyed with almost no dialogue.

As I mentioned, the third story mostly didn’t connect with me, though it too had its interesting moments, its pleasing visuals.

Also worth mentioning as far as the style is that the second section—set in 1911—is silent (except there’s a musical soundtrack, and during the shots where a woman is playing a stringed instrument and singing there is audio for her), and uses title cards for the dialogue, in the fashion of old silent films. However, there’s no effort beyond the title cards to give it the feel of a silent film. It’s not black and white, the film’s not artificially made to look aged, the cinematography isn’t modeled after the style of a century ago, etc. It looks like the other two stories except that instead of being able to hear the people talk, you see them move their lips and then read what they said on a title card.

Although mostly there’s a lot to like about the style of this film, that element I’m more neutral about. It maybe strays toward the gimmicky. It might have been an interesting move to make each segment look like a film from its era across the board, but I’m not sold that there was much of a point to just doing the dialogue in silent movie fashion for the one story.

Anyway, it’s a film that was more grueling than most for me to get through, so there’s a limit to how positive an evaluation I can give it, but in many respects it’s just a really well done, intelligent, beautiful movie. It’s one of those films where I’m aware I’m seeing the work of a truly talented filmmaker.